BUILDING ON LEGACIES: INTERVIEW WITH DIRECTOR SAM POLLARD

Editor-turned-director’s latest work features late Mayor Maynard Jackson

There’s something synchronistic about a trailblazing African-American mayor, who paved the way for a trailblazing African-American president, having his story told by a talented editor-director, who himself came up through the influence of a legendary African-America director.

Sam Pollard’s timely documentary Maynard, then, is an exemplar of black legacy all around—in front of and behind the camera. We read frequent reports of the current presidential administration on a quest to erase the legacy of the country’s first black president. Pollard’s film asserts that Barack Obama’s legacy, in part, is a continuation of strides began from folks like Maynard Jackson.

“Listen,” Pollard says, “looking at Maynard in hindsight is a breath of fresh air.”

CHECK OUT MY REVIEW OF MAYNARD

Maynard Jackson Jr.’s story is long overdue for the screen. In 1973, the charismatic, unflappable politician was elected mayor of the city of Atlanta, becoming first African-American to lead a major southern city. Jackson held the post for three terms and by the time of his death had changed the course of politics.

Maynard Jackson

Pollard’s film illuminates a political terrain fraught with racial discord, political in-fighting, complex alliances, both black and white. Sound familiar to today’s politics? And yet, Maynard inspires hope. Our nation’s been through this before, it says, and we have come through the other side.

Even before becoming a longtime editor of the films of director Spike Lee, Pollard had a winding career in editing. Before Lee, Pollard spent 20 years doing low-budget work with vanguards like the late Bill Gunn. But working with Lee for more than 20 years has provided Pollard with “a sense of how to tell a story,” he says. “Being an editor has had a very positive impact on my directorial career.”

The Emmy winner (his “Slavery By Another Name”), four-time Peabody Award winner and Academy Award nominee has produced films on playwright August Wilson, singer Marvin Gaye and author Zora Neale Hurston.

In Maynard, Pollard’s command of his material—with assistance from his editor Jeff Cooper and cameraman Henry Adebonojo—is on display. The documentary vibrates with a sense of the era—its roiling racial politics, its music, the clothes. Maynard Jackson, tall and broad, uses carefully chosen words, commands audiences with his articulate speeches and forthright assertions. Sound familiar? We see Jackson, successful in high school and college, grandson of famed civil rights leader John Wesley Dobbs, primed for greatness.

There would be stumbles along the way. Facing defeat after a run for the Georgia senate, a young Jackson dusted himself off, and turned the experience into a successful campaign for mayor.

Pollard uses archival footage to great effect. I was gobsmacked by footage of a portly Jackson in the ring with Muhammad Ali for a promotional boxing match. News footage and interviews of the Atlanta child murders that rocked Jackson’s second term remain potent. And Jackson’s legacy-burnishing renovation of the Atlanta airport into an international hub truly speaks to his lasting accomplishments.

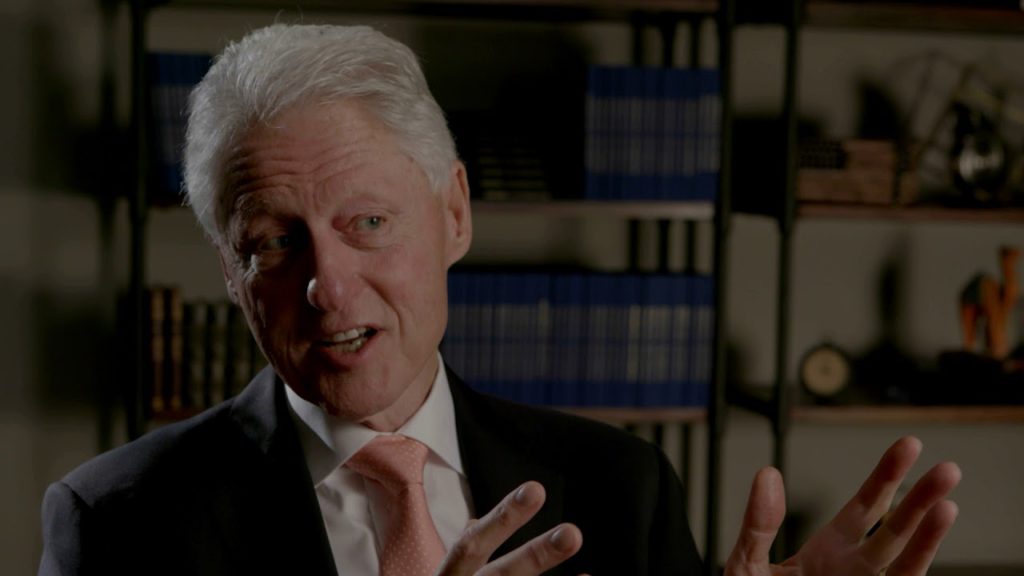

But it’s the talking heads that give weight to Pollard’s film and Jackson’s story. Famed mayors Andrew Young and Shirley Franklin. Civil rights heavy-hitters Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton. Former President Bill Clinton. Attorney Vernon Jordan. Pollard gets them to speak personally about Jackson. The voices of Jackson’s family wring true intimacy from the proceedings. Jackson’s son, daughters, ex-wife and widow bring the Jackson legacy into focus. Their contributions went beyond speaking in front of the camera, though. It was the Jackson clan that brought Maynard to life. Pollard says he was sought out by the family to bring the story of the late mayor to the screen.

“The family reached out to me,” he says. “They were looking for someone to help produce a film about their father.”

The family understood its patriarch’s place in history. A quote by Jackson’s daughter Bunnie Jackson Ransom—“He was the Obama before Obama”—has been used in some promotional materials.

Maynard was not a perfect mayor. He belatedly contended with a corrupt cabinet member, and seemed to lose his zest for politics during his apprehensive third term. Pollard intended to create a full portrait of the man.

“The easy part would be to not have complexity,” he says. “I wanted a very rounded perspective.”

To that end we see former mayors still touched Maynard’s influence, Bill Clinton’s eyes brighten as he relates a Jackson anecdote as only he can. And the scene in which the news of Maynard’s untimely death reaches each of his family members is masterfully filmed and edited.

The documentary gained from what Pollard calls the “benefit of living witnesses.” The film boasts participation from other trailblazers of the era.

“They are still alive. All these former mayors touched by him,” he says. “You can hear directly from people who pass on his legacy.”

Up next for Pollard is a feature film on the life of Bert Williams, a black entertainer from the Vaudeville era. The Bahamas-born Williams rose to become one of the most popular comedians of his day. Pollard’s film, sure to be as provocative as Spike Lee’s Bamboozled, is in the fundraising phase.

Maynard debuts Nov. 16 at DOC in NYC.

Official site here

Sam Pollard’s filmography here

| Marvin Brown’s Movie Review Archive

I’m not sure, but don’t miss the opportunity to give this overlooked drama/thriller a chance now that it’s available on DVD. Be warned, though, that like the brutal, uncompromising original, its taboo subject matter revealed in its final act is not for all sensibilities.

I’m not sure, but don’t miss the opportunity to give this overlooked drama/thriller a chance now that it’s available on DVD. Be warned, though, that like the brutal, uncompromising original, its taboo subject matter revealed in its final act is not for all sensibilities.