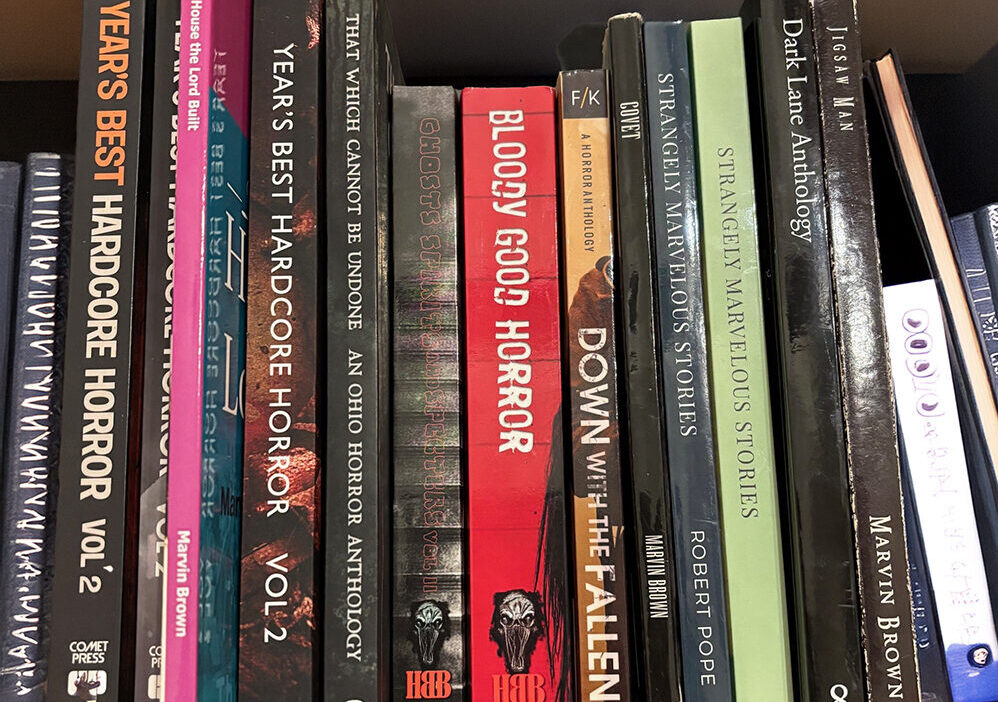

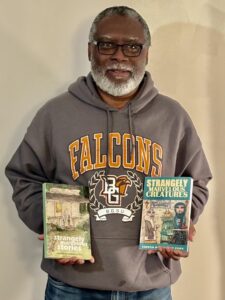

My short story “The Wet Knot” appears in the anthology Strangely Marvelous Creatures, edited by Robert Pope. Click here to purchase.

Marvin Brown at Goodreads.com: Find out what the author’s currently reading, check out some of his favorite books, read his book reviews and get his recommendations on great fiction. Click here.

“Hope” Inspires in Times of Struggle

Teen Director Kalia Love Jones seeks to empower with debut film ‘The Power of Hope’

Kalia Love Jones

These days, survival seems to be drawn down to basic actions—you’re either cordoning yourself off from a dangerous virus, taking care of those who have caught the virus, or deciding you’re not going to let something as annoying as a global pandemic get in the way of your summer thrills. Still, there are some who survive through their creative spirit, and choose to inspire through their art.

In any era, the arrival of a 12-year-old filmmaker is quite a feat; in the time of Covid-19, it’s a reminder of why we power through uncertainty and obstacles. It is, as Kalia Love Jones intends her film to be, empowering. So “The Power of Hope” arrives in time to inject a little motivation into our toughest days, and it comes from a preteen talent who is as inspiring as her tale.

In the animated short, we met a young black girl, not unlike the film’s director, with wide-eyed dreams. The girl wants to become an architect, but those dreams are jeopardized when her mother becomes very sick. The girl’s world spirals into uncertainly—about her mother’s health and about her own dreams. In this fearful time, the girl finds support from the words of Michelle Obama. Through the former first lady’s powerful speech, the girl is empowered to make her dreams reality.

The film, like most memorable animation, like the best of Pixar’s work, relies on strong visuals, sound and music to carry its story. The only dialogue we hear is Mrs. Obama’s stirring words

Kalia, who hails from Los Angeles and has an older brother and younger sister, undertook the project with the wind at her back—her talent to spare and the support of her parents. She saw “The Power of Hope” as an opportunity to combine two of her many passions, music and animation.

“I want to be an animator when I’m older,” says the girl who’s been drawing for as long as she can remember. “Animation is the best way to get people my age to pay attention.”

Kalia spends hours drawing and studying films. She says, “Live action is interesting, but animation is my calling.”

Filmmaking, even short films, is a marathon not a sprint. It’s not work for impatient folks. The motion picture was produced in laps. It took Kalia a month to write. Then the animation, which she supervised, took another six to eight months. She spent a month more working on the music.

Events in the film were fictional, even though the character was influenced by Kalia herself.

“I drew the story boards and made the character look like me,” she says.

Her father’s support for the project was particularly useful when it came to the film’s soundtrack. He put her in touch with Grammy-nominated producer Ben Franklin.

“He’s friends with my dad. He wanted to be a part of the film,” Kalia says. She and Franklin co-wrote the movie’s theme song, which is now available on all major music platforms.

“It was fun,” she recalls. Of course it was. Music is another of her passions. “I love music. Music is its own language.”

Kalia finds filmmaking and music production complementary art forms.

“They work well with each other.”

As for her first time in the director’s chair, it was challenging. “It was difficult at first,” she says of having to give order to adults. “Once we realized the whole team shared the vision, things got easier.”

If the rigors of filmmaking weren’t challenging enough, Kalia’s project came about during a pandemic. Doing promotional work for the film has been hampered by the outbreak. It’s prevented her from taking opportunities push the film, and limited meetings with people in the industry. And like many of us, quarantine has kept her isolated from many of her friends.

“I haven’t been able to talk with my friends,” she says. “I don’t really know how they feel about the film.”

Above all, like her film, Kalia is all about empowerment. “I want people to feel empowered, to feel the confident to overcome their obstacles.”

Her influences are rich with women of note: director Ava DuVernay (“Selma”, “A Wrinkle in Time,” “When They See Us,”), animator Rebecca Sugar (creator of “Steven Universe”), Michelle Obama and her mother.

“My mom influence is on more than the film,” Kalia interjects. “She influences my life. She’s a strong woman in my life who is very inspiring to me.” A little bit of her mother is drawn into the mother in the film.

Kalia had already been an admirer of Michelle Obama when she came across one of the first lady’s speeches while doing research for her film. “She’s always been an inspiration to me.” Mrs. Obama’s spoken words provide voiceover that punctuates the emotional visuals.

Even amidst concerns of the outbreak, it would be hard to miss the surge of protests and activism against racial inequality, particularly the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. The shocking death of George Floyd under the knee of a police officer has lead to a hot summer of marches and clashes. Kalia support the protests. “One of the reasons I made the film was to give more representation to our stories,” she says. “Our stories are valuable and black lives are valuable.”

She is a girl full of passion. Some of her other passions include piano, honors band, where she is first chair flute, and gymnastics. She’s an eight-year gymnast who trained with former U.S. Olympian Chris Waller at his gym in Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, Kalia plans to continue perfecting her crafts while she deliberates on her next project. As the dust settles on a year of illness, death and protest, it’s comforting to know the creative spirit is alive and well, and particularly that it resides in our youngest, a soon-to-be 13-year-old brimming with passion and not willing to wait or settle in presenting ideas that inspire.

Learn more of Kalia Love Jones’ “The Power of Hope” at the film’s website: www.thepowerofhopefilm.com

| Marvin Brown’s Director Interviews

| Marvin Brown’s Movie Review Archive

The short film is narrated in voiceover by the person we’re watching as she directly addresses the audience watching her. Kailee’s eager for stardom and boasts of her social media following—which isn’t really that large, but larger enough to give her hope. The back of her car is filled with empty cans of Lacroix, of course, and parking violations, but she looks and plays the part of a star.

The short film is narrated in voiceover by the person we’re watching as she directly addresses the audience watching her. Kailee’s eager for stardom and boasts of her social media following—which isn’t really that large, but larger enough to give her hope. The back of her car is filled with empty cans of Lacroix, of course, and parking violations, but she looks and plays the part of a star.