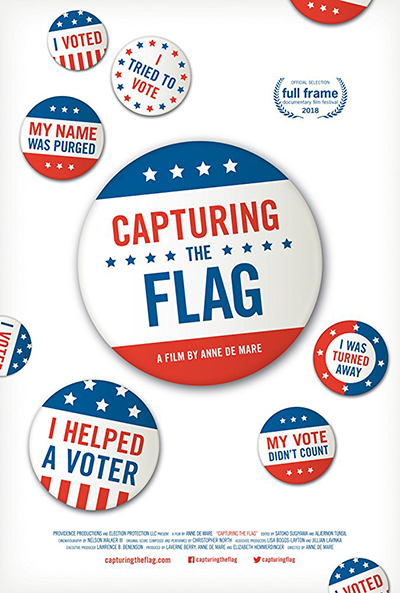

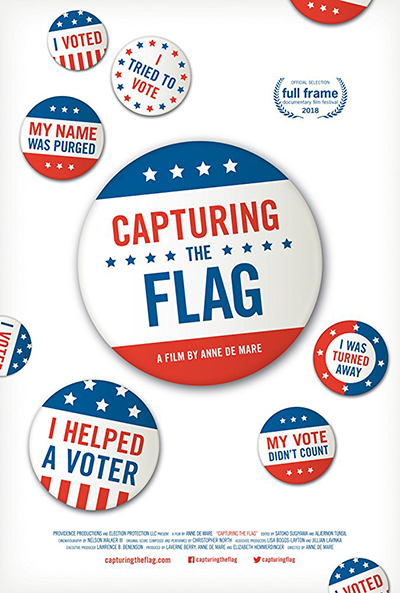

Capturing the Flag (2018)

Unrated

Volunteer voter protection worker, Brooklyn-based entertainment lawyer and producer of Capturing the Flag, Laverne Berry. Photo credit: Nelson Walker III

New York attorney Laverne Berry, saw something at an election polling site years ago that jolted her from her comfortable contribution of driving people to the polls. When one of her charges had trouble walking, a janitor on site took it upon himself to use a pushcart and chair to get the woman to the polling booth.

“If he could do that on a day when that’s not his job,” Berry determined, “I can take some time off every election to do something.”

“If he could do that on a day when that’s not his job,” Berry determined, “I can take some time off every election to do something.”

In Capturing the Flag, Berry and three other “voter protection volunteers” are documented during the lead-up to and through the 2016 election from their on-the-ground perspective in Fayetteville, North Carolina, polling districts. Director Anne de Mare’s fascinating and sober documentary fights an undercurrent of foregone conclusion, but provides pointed insights into our election system and the soldiers who take up the challenges of making votes count.

CHECK OUT MY INTERVIEW WITH DIRECTOR ANNE DE MARE

De Mare and her cast navigate subject matter that should be important to not simply those still distraught about the results of the 2016 election; setting aside partisanship to fairly critique our voting process should matter to every citizen.

Joining Berry on her quest is volunteer Steven Miller, an attorney and longtime friend. Miller, a white man, and Berry, a black woman, communicate with an ease certainly found in lifelong friends. En route to North Carolina we meet volunteer Claire Wright, an attorney and recent naturalized citizen. This is her first U.S. election and her first visit to North Carolina. Writer Trista Delamere Mitchell eagerly joins the group on the ground.

De Mare, along with animator Sean Donnelly, use visual aids to provide an “election day” sense of urgency to the documentary. A graphic counter along the bottom of the frame tick off months, then days, then hours before election results.

Almost immediately the team runs into an ongoing controversy at an early voting site in Fayetteville. The local NAACP has accused the state board and three county election boards of illegally removing thousands of people from voter rolls. The purge, they say, is primarily affecting voters of color.

Berry laments the inconsistent voting rules and methods from state to state. It makes protecting voter rights “daunting.”

A 2013 Supreme Court decision invalidated Shelby County v. Holder, a provision of the Voter Rights Act of 1965. That 2013 decision limited supervision by the Justice Department over states that had demonstrated relentless efforts to curtail black people from voting. Within weeks of the ruling, several states began establishing new voting restrictions—more stringent photo ID laws, limits on third-party voter registration, limited rights for those with past criminal convictions, shuttering polling locations across states. The very day of the decision, Texas began efforts to redraw boundaries for congressional and state house districts.

We watch as Berry bravely heads alone into the breach—a polling site in an all-white community littered with yard signs for Republican candidates. Yet, she reminds herself that her mission is to insure fair voting, regardless of party affiliation. She is regarded with caution at first, but her eagerness to help, earnestness and time pushes her through resistance. Miller, at different polling site, faces similar challenges from black people.

For a time, then, the film becomes a microcosm of the passions, absurdities and contradictions of the U.S. election system. A young polling judge at a precinct is initially curt and forceful with Miller, who’s assisting folks outside the polling site. The young man regards the older one as an outsider, a troublemaker. But as the day goes on, and both men doggedly undertake their responsibilities, they seem to accept each other’s roles. The strident young judge in fact, is revealed to may have overreacted due to the stresses of heading up a polling site for the first time. In the end, Miller joins him inside the now-closed precinct as polling officials search for an errant ballot.

For a time, then, the film becomes a microcosm of the passions, absurdities and contradictions of the U.S. election system. A young polling judge at a precinct is initially curt and forceful with Miller, who’s assisting folks outside the polling site. The young man regards the older one as an outsider, a troublemaker. But as the day goes on, and both men doggedly undertake their responsibilities, they seem to accept each other’s roles. The strident young judge in fact, is revealed to may have overreacted due to the stresses of heading up a polling site for the first time. In the end, Miller joins him inside the now-closed precinct as polling officials search for an errant ballot.

The team’s journey is intercut with efforts from the local branch of the NAACP, including a press conference by chapter President Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II. Barber and others are pushing back against subtle and blatant attempts to suppress the minority vote.

Amid these early voting machinations, President Obama visits Fayetteville for a rally that for me stood as a contrast to the divisive rallies that have sadly become the norm. When an elderly man wearing a military uniform riles up the crowd with his Trump sign, Obama playfully admonishes the agitated crowd and reminds it that, 1) free speech should be respected in the U.S., 2) veterans deserve our respect, 3) elderly people should be respected as well. He famously concludes: “Don’t boo, vote!”

Meanwhile, foreign-born Wright registers disappointment, having recalled practicing law in post- Apartheid South Africa when that country’s courts looked to U.S. law precedents as a guide to building South Africa’s new constitution. “I thought that the U.S now, after the civil rights movement, was an egalitarian society,” she says. “Living here has made me realize it is not at all.” It is crushing to watch Wright trying to help an African-American woman, having been referred to a third precinct and still not able to cast a ballot, who throws up her hands and says she has to get back to work instead.

I like that de Mare allows her subjects to display their professional and ethical commitment to their tasks, while reminding us that they are also citizens, party affiliates, who care not just about voters but the outcome of the election. Since we already know the fateful outcome of the 2016 race, it’s with some dread (or joy, if Trump was your guy) that we relive the day while Berry and the team face it for the first time: the certainty that the math is in Hillary Clinton’s favor, the surprise that Donald Trump is doing better than predicted, the rising suspicion that the calculus was wrong, that working-class sentiment was misjudged; the shock and disbelief of the results.

We’ve walked with Miller as he remained level-headed and professional throughout the day. Not until the night of election results, when he explodes into anger, confusion and disappointment, do we see the partisan side he’d left off the field while attending to his duties.

De Mare, an award-winning director (The Homestretch, 2014), has taken us back to a fateful moment in U.S. history to allow us to relive it at the ground level and in personal terms. With cases before the courts (including our top court) on issues of gerrymandering, alleged attempts to manipulate the upcoming census, as well as looming critical midterm elections, de Mare’s film couldn’t be timelier.

Capturing the Flag has its world premiere at the Full Frame Documentary Film Festival 2018.

| Marvin Brown’s Movie Review Archive

The short film is narrated in voiceover by the person we’re watching as she directly addresses the audience watching her. Kailee’s eager for stardom and boasts of her social media following—which isn’t really that large, but larger enough to give her hope. The back of her car is filled with empty cans of Lacroix, of course, and parking violations, but she looks and plays the part of a star.

The short film is narrated in voiceover by the person we’re watching as she directly addresses the audience watching her. Kailee’s eager for stardom and boasts of her social media following—which isn’t really that large, but larger enough to give her hope. The back of her car is filled with empty cans of Lacroix, of course, and parking violations, but she looks and plays the part of a star.

Kai (Joshua Glenister) certainly seems to have a bright future. He’s a writer with burgeoning talent, despite his fears of pushing through his insecurities. Kai hangs with and gets high with Sammy and Megsy. Sammy (Charlie Frances) drives a milk truck and initially seems to balance his dreams and reality. Megsy (Jack Gouldbourne) is the stereotypical foulmouthed, loud-speaking, trouble-seeker who seems to exist to constantly plunge his friends into unnecessary situations. It’s a testament to Gouldbourne’s performance that Megsy ultimately escapes the archetype foisted upon him.

Kai (Joshua Glenister) certainly seems to have a bright future. He’s a writer with burgeoning talent, despite his fears of pushing through his insecurities. Kai hangs with and gets high with Sammy and Megsy. Sammy (Charlie Frances) drives a milk truck and initially seems to balance his dreams and reality. Megsy (Jack Gouldbourne) is the stereotypical foulmouthed, loud-speaking, trouble-seeker who seems to exist to constantly plunge his friends into unnecessary situations. It’s a testament to Gouldbourne’s performance that Megsy ultimately escapes the archetype foisted upon him.

Director Nathan Catucci has seeded his film in those opening sequences. Now, we are introduced to other main characters.

Director Nathan Catucci has seeded his film in those opening sequences. Now, we are introduced to other main characters.

An award-winner on the film festival circuit, Magical Mystery is cleverly inked on cocktail napkins. Every now and again we get a pull-back that reveals the napkins among an arrangement of plates and utensils on a table.

An award-winner on the film festival circuit, Magical Mystery is cleverly inked on cocktail napkins. Every now and again we get a pull-back that reveals the napkins among an arrangement of plates and utensils on a table.